With our very particular role as advisors, enablers and creatives working across stakeholder groups, architects are particularly well placed to respond to the environmental challenges faced by humankind.

Environmental broadcaster Sir David Attenborough recently said:

‘We are at a unique stage in our history. Never before have we had such an awareness of what we are doing to the planet, and never before have we had the power to do something about that.’

In order to act in the interest of the common good (and the good of the next generation), we need to be prepared to put our own economic interests aside. This includes challenging pre-conceptions and advocating for an ecologically sound solution to our clients’ needs, even when that solution may not include the design for a new building.

In practice, this means evaluating how our designs will act as part of the ecological systems around them; it means embracing flexibility and adaptability in our designs to accommodate changing occupant needs; it means considering how building fabric will be repaired as part of its alignment with natural systems. It also means accepting (known and calculated) compromise and imperfection, and a looser approach to design where this results in a more ecologically sound response.

Carl Elefante, former president of the American Institute of Architects once said: ‘The greenest building is the one that already exists’.

Elefante will have consciously chosen the term ‘green’ over the term ‘sustainable’. He knows that language matters. He speaks to the problem that a building can have many demonstratively sustainable features and yet be ecologically detrimental, whereas the retention or adaptation of an existing building may be the most ecologically sound solution.

Since the formalisation of the profession, architects have worked across disciplines, provoking innovation and drawing together the various specialisms that go into the design of buildings and cities into a greater and coherent whole. Our specialism has always been to have no particular specialism, but to consider the big picture and to take the long-term view. Ecology in essence is about balance and we have the capability, tools and intellect to be that balancing force.

We have recently been working on two projects which exemplify our approach to ecology. Both the result from close collaboration with educational charity Global Generation, who use themes around ecology to build a more resilient society and empower young people to become change makers in their own communities. Global Generation’s success relies on reinforcing commonalities between people, across social- and professional boundaries.

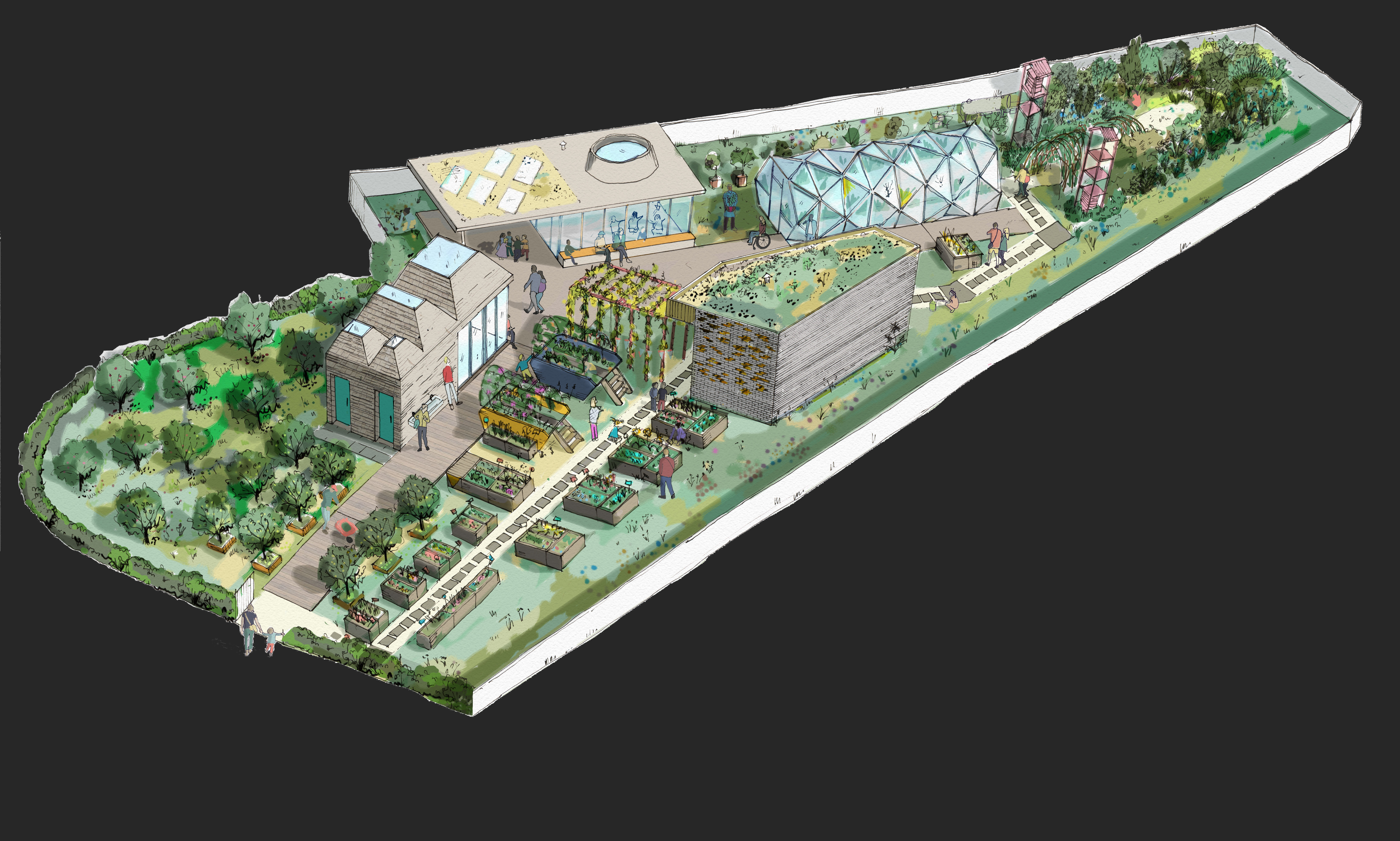

After over a decade moving between temporary sites in Kings Cross, the charity was finally given a piece of land to build a permanent garden. In a series of workshops, we developed a family of small buildings arranged along a common boardwalk, all set amidst an educational ecology garden, itself wedged between two mainline railway lines. We defined nine ecology zones, each providing a distinct habitat condition for urban wildlife and pollinator food throughout the season. This approach underpins an educational curriculum, serves as a means to maintain and monitor biodiversity and helps to manage invasive species.

A wildlife maze at the end of the garden is inaccessible to visitors, providing habitat to reclusive animals and ground-nesting species. The buildings themselves are constituent parts in the garden’s curriculum. They touch the ground lightly and integrate with the landscape. Materials and construction methods were selected with consideration for their whole life footprint, and include rammed earth construction, intensive green roofs, timber structures and facades. Rainwater collection will minimise the use of mains water in the garden, while a wide-ranging community engagement programme is building advocacy for the environmental credentials of the site and its core message.

Meanwhile, we have also been working on a new ecology garden in Canada Water with Global Generation and British Land. The Paper Garden will bring ecological benefits to the site by ensuring that

Any structures built are entirely made from reclaimed materials, including the re-use of an existing industrial structure on site and surplus from construction sites elsewhere. For this purpose, we are compiling an inventory of components from various buildings that are due to be demolished locally.

The garden will be watered entirely using rainwater collected on site (in reclaimed rainwater butts).

Planting will be organic and pollinator-friendly so as to establish a diverse urban ecology which will inform planting initiatives across British Land’s wider masterplan.

There will be extensive opportunities for co-creation and participation including close collaboration with the TEDI London engineering program, Greenwich University’s landscape department, Global Generation’s own Generator Program. Opportunities for local schools, families and residents are designed to inspire participants to become advocates of urban ecology.

At Canada Water, our contribution is just one miniscule part of a powerful multi-lateral engagement program involving thousands of individuals. Despite its modest scale, we see it as an essential component that puts into physical and visible form an all-encompassing approach to promoting urban ecology.

Helping a wider public to appreciate the natural environments around them will be a key measure in combating biodiversity loss and the climate crisis. We have found that an engaged design process can bring provide far-reaching opportunities to campaign with an impact that transgresses geographic site boundaries, and a legacy that will outlast the duration of a project.