Theatre and architecture have one very significant thing in common:

they both set the scene for dialogue and social exchange. Practising across disciplinary boundaries helps us to learn from one to advance the other.

When tracing the origin of architectural practice in England, Inigo Jones’ work during the Renaissance stands out as a significant milestone. Carol Strickland and Amy Handy credit him as ‘the first significant architect in England in modern times’. Interestingly, Jones began his career as a set designer, conceiving performance spaces for some of the grand Royal Masques. His motifs were heavily influenced by his travels to Italy, where he studied classical architecture and the Vitruvian principles of proportion and symmetry in buildings. Jones’ stage sets were significant in introducing classical architecture to England during the 16th Century, when travel to Italy and Greece involved an arduous journey that few were able to undertake. Jones’ efforts as a set designer paid off when he finally won the commission to design the Queen’s House and the Banqueting House in Whitehall and later became involved in the conception of Covent Garden.

Most of our work during the early years of Jan Kattein Architects was in set design. The practice won an important international theatre design award in 2005, and subsequently designed for theatres and opera houses in Graz, Austria, Munich, Cottbus, Düsseldorf and Hamburg, Germany. Although our theatre work was not concerned with the introduction of a new architectural style, theatre practice continues to inform the ways we think about our practice as architects.

The close alliance between theatre and architecture has been widely documented. Architectural historian Helen Furjan describes how 18th Century Architect Sir John Soane invited guests to candle-lit performances at his house in Lincoln’s Inn Fields, London where visitors became actors and the walls of his house the screen on which their shadows were projected. 19th Century German philosopher Walter Benjamin has compared the city to ‘a popular stage’, and in his influential book Delirious New York, Rem Koolhaas discusses the making of modern Manhattan as a screenplay in which politicians, industrialists and the city’s architects appear as protagonists.

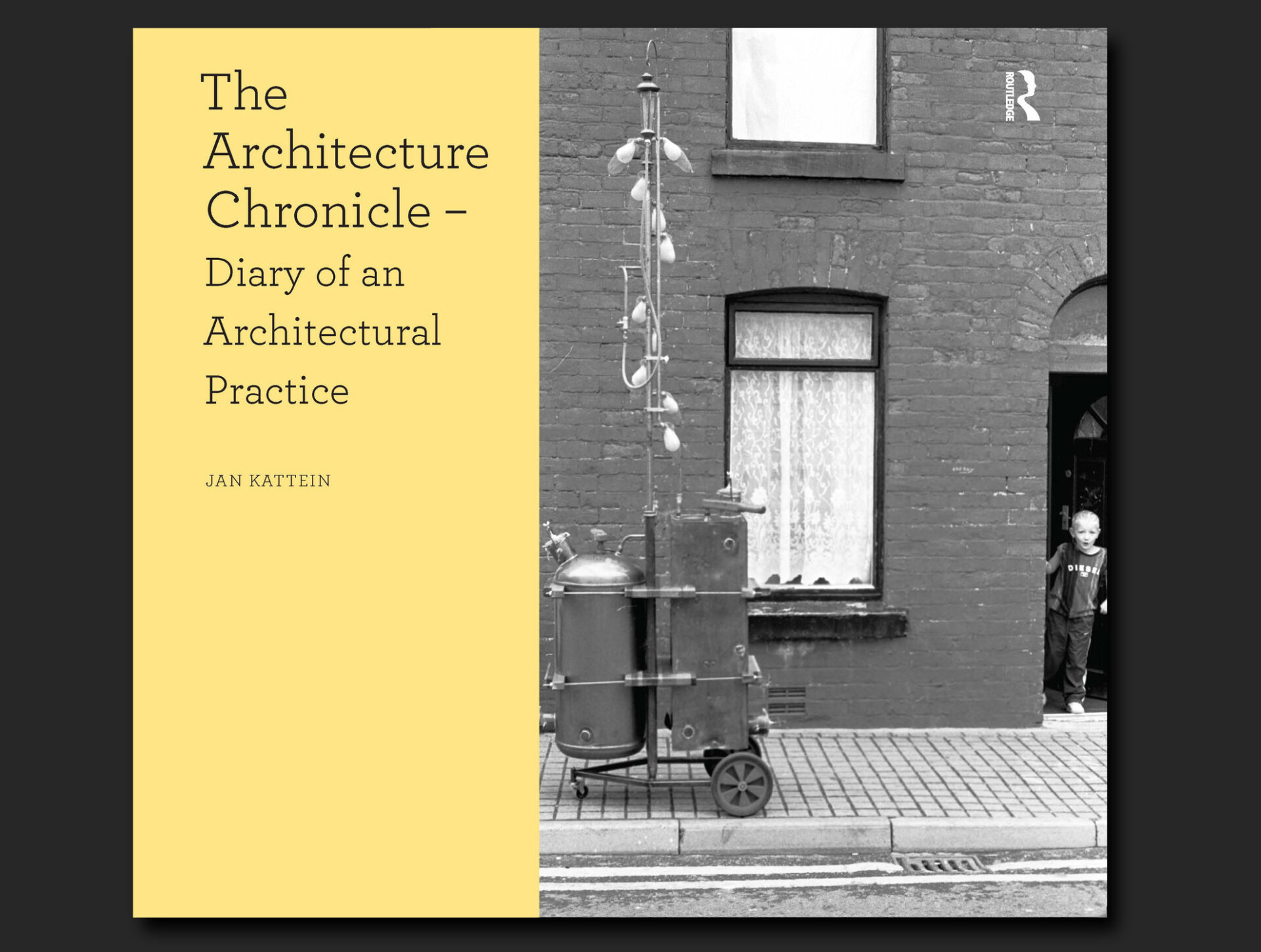

We remain particularly fascinated in the moments where these two disciplines align. Jan’s book, the Architecture Chronicle, Diary of an Architectural Practice interrogates the designer’s role in the practice’s early set design projects, and goes on to define three distinct characters. The architect-inventor brings ideas and innovation. Meanwhile, the architect-activist transgresses disciplinary boundaries to widen the definition of architecture. Finally, the architect-arbitrator engages others to realise the project. The book concludes that good spaces are the result of a balanced contribution from all three members of the trio.

Not all characters need to be vested in one and the same person, but as a practice, we know just how important it is that our projects benefit from a balanced team working collaboratively. This is why we have put in place a project-peer system which assigns a sponsor, a project architect as well as a project peer to each of our projects. This approach allows team members to learn from each other and to better manage workloads. Design is largely a subjective art, working as a team of equals means that our designs benefit from multi-lateral interrogation and are ultimately shaped by a balanced view. Much of our work is about communication. We are much more successful in engaging others by explaining ideas and concepts using a multitude of voices.

Theatre is first and foremost a social event. Composing the relationships between the protagonists and between characters and audience is the director’s responsibility, yet the scenery also plays a significant supporting role. The same is true for architecture. The placement of solid and void, permanent and temporary elements can either facilitate or undermine social exchange. As architects we put great effort into imagining how the places we design will be used. We work closely with stakeholders to test our presumptions and to make sure our designs provide for unforeseen and unpredicted uses (and users).

Walter Benjamin’s description of the city paints a lucid picture: ‘Buildings are used as a popular stage. They are all divided into innumerable, simultaneously animated theatres. Balcony, courtyard, window, gateway, staircase, roof are at the same time stages and boxes.’

In the theatre, design is communicated primarily orally. A physical model is of great significance, but scale drawings only have a secondary function. Team meetings revolve about the model with actors, director and technicians all gathered in the round. As architects, we still invest ourselves in model-making, with our own dedicated workshop on site. Models are inclusive and trusted spatial representations which allow everyone to participate in design discussions. We have found that – unsurprisingly perhaps – drawings are often treated with suspicion or disdain by those less practiced at translating abstract lines on paper into spatial concepts.

The design test is a well-established milestone in every theatre production. It involves the ad-hoc rigging of set designs on stage well in advance of final sets being made in the theatre workshop. All team members including the various technical departments have the opportunity to scrutinise the design with an immersive walk through the full-scale mock-up. In Switzerland, a Baugespann is an important part of the approvals process for new buildings. A combination of brightly coloured strings, scaffolding and rigs are used to ‘draw’ the outline of a proposed building at full scale into the air. Stakeholders have the opportunity to interrogate the impact of any proposed structure on site before permission is granted. At JKA we believe in full scale prototyping. In collaboration with our contractors and fabricators we often prepare 1:1 segments or samples of critical design elements. There is nothing more powerful than reviewing a colour palette on site, in the actual conditions in which the building will stand, to question junctions between modular units at full scale or to trial a space or operational concept before rolling it out across a larger site.

At its best, theatre tells stories that linger in the memory long after the curtain falls. Places can also tell stories. We often use reclaimed materials for environmental reasons, but also to continue a compelling narrative building on the previous lives. In a similar fashion, working with communities on design projects gives people a voice in shaping their environment, but it is the physical memory of their involvement and investment that contributes an enduring connection to the project after it is realised on site.